- Grantt Bedford is Director of Safety, Environment & Quality for the U.S. branch of the Italy-based oil and gas company Eni. Working in such a high stakes industry has made him appreciate the role that robust safety programs can play in saving money and lives.

- Leaders who treat their organization’s safety program as an annoying obstacle are missing a strategic business opportunity. Preventing accidents will save money in the long term and keep regulators happy.

- The true purpose of a safety program isn’t to record accidents, it’s to prevent them. Use data to predict accidents before it’s too late, and track preventative methods — e.g. inspections and behavior-based safety observations (BBSO) — across the organization.

All safety professionals bear an enormous responsibility in safety programs. After all, life and limb are literally on the line.

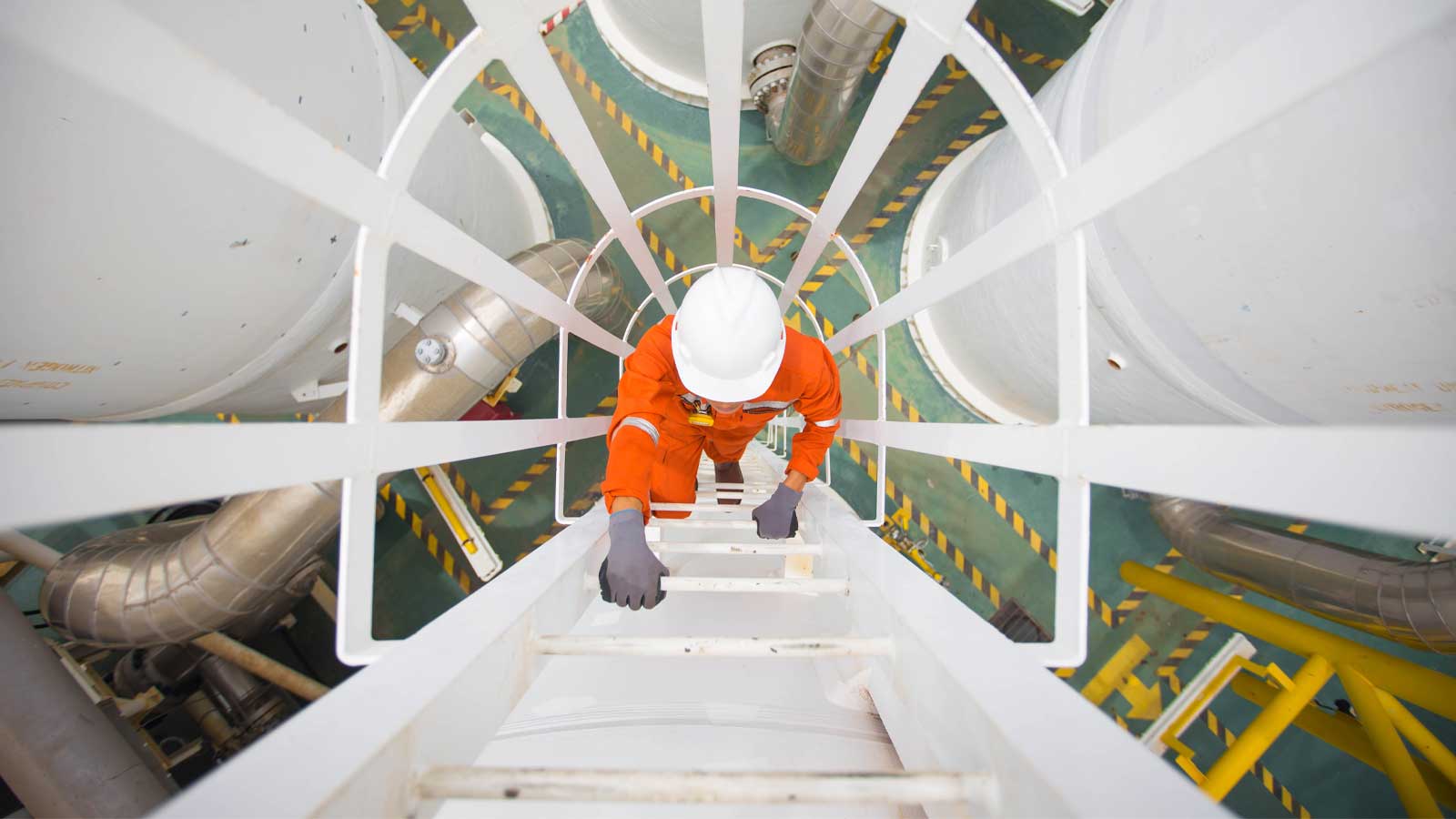

However, it’s fair to say that some industries come with higher stakes than others. As Director of Safety, Environment & Quality for the American branch of Italian oil and gas company Eni, Grantt Bedford is responsible for the safety of people working in one of the world’s most high-risk industries.

Precisely because the risks involved are so great, oil and gas companies are more willing to invest in safety programs than counterparts in other industries. More than that, leaders see a robust safety program as a strategic business move, reducing the likelihood of expensive accidents and regulatory interference.

Grantt believes that the innovative approach that his industry takes to safety holds lessons that are relevant to business leaders and safety professionals across the board.

Based on an episode of the No Accident podcast, here’s how to use data to predict and prevent major accidents, and how to alert leaders to the importance of a proactive safety program.

Being Strategic About A Safety Program Is Good for Business

In the past, focusing on safety was seen as an impediment to success. From this perspective, time and money spent meeting exacting regulatory standards was time and money taken away from revenue-generating parts of the company.

However, modern executives are learning that safety precautions are an unavoidable cost of doing business.

At a minimum, Grantt argues that leaders must learn to treat safety as they would any other business process. If you don’t resent granting a budget to the marketing department or making sure finance has all the information it needs to file the company’s taxes, don’t resent the safety department when it makes similar demands.

This baseline acceptance of the role of the safety department is just the first step, Grantt says. The most forward-thinking leaders understand that a strong safety program is a strategic business asset.

The oil and gas industry provides an interesting example of how taking the lead in safety can make a business more effective. It’s one of the most regulated industries, but Grantt says that even if the government didn’t hold it to such a high bar, the largest organizations would most likely internally enforce similar standards anyway.

For one thing, leaders understand that if they don’t act to prevent disasters, the moment one occurs, the government will introduce tighter regulations. When you stay ahead of the game, you play on your own terms. You have to address safety one way or another, and it’s preferable to build your own approach than have the government dictate it to you.

The other factor that has pushed oil and gas companies to embrace safety programs more readily than other industries is scale — of both profits and disasters. Oil and gas generate high revenues, but as Grantt points out, the work is so high-risk that the dangers are also vastly higher than in most other industries.

These environments come with job-specific risks, such as fires and explosions. On top of that, a relatively mundane accident can be significantly more serious on an oil rig or a gas pipeline, because the hazardous and isolated nature of these workplaces increases the danger.

The combination of large profits and high risks means that oil and gas companies have both the money and the incentive to prioritize building robust safety programs. Preventing accidents protects profits.

Be Proactive to Prevent Accidents

Of course, not every company is operating with such large profits or risks as those in oil and gas. However, the same logic applies whether someone is injured on an oil rig or a construction site. Accidents cost money, and can be personally devastating for victims. Taking steps to prevent accidents can save these costs.

The accident-prevention process is twofold. You need a way to predict accidents before they happen, and you need to put systems in place that encourage safe behavior and identify risky behavior.

Grantt has two specific methods for approaching these challenges:

Study Data to Forecast Safety Hazards

Health Safety Environmental (HSE) data can give you insights into:

- Types of accidents

- Rates of accidents

- The conditions in which accidents commonly occur

- The severity of accidents

Knowing these can help you predict major accidents before they happen. For example, Grantt highlights falls — a leading cause of death in the oil and gas industry. He explains that if you look at the HSE data, you can see:

- Where each fall occurred — was it at ground level or high up?

- What were the conditions?

- How severe were the injuries?

- What are the rates of these incidents?

Pulling out these insights can make it easier to see patterns that are obscured in the raw data. For example, if a significant number of people have been falling in a particular part of the rig, under certain conditions, and injuries are getting increasingly severe, you can make the case that someone will likely have a very serious fall at some point.

This approach puts lagging indicators to good use in preventing future accidents. And being able to put numbers to your claims can help you make a stronger case to leadership than anecdotal evidence alone.

Keep Score of Safety Efforts

You can also prevent accidents more broadly by actively monitoring general safety practices. Grantt calls these “proactive efforts.” Examples include:

- Inspections

- Safety meetings

- Behavior-based safety observations (BBSO)

- Job safety analysis (JSA)

Grantt recommends using simple scorecards to track how often these are carried out on a weekly and monthly basis. Break it down by project, group, and the organization as a whole, to get both a detailed and high-level picture of where safety messaging is lacking.

Make It Personal for Leaders

If you’re working under leaders who haven’t grasped the importance of safety, dumping the data on their desk won’t bring them around. You have to paint a picture for them that makes it clear why they need to care.

As Grantt puts it, make it personal. Explain the very real consequences accidents can have for the company. These include:

- Injury or death of a worker: In most cases this would be enough to persuade leaders to take safety programs seriously.

- Financial implications: For example, compensation to the worker or their family, increased insurance premiums, and the cost of replacing equipment.

- Workforce morale: Injuries and deaths take a toll on the entire workforce, reminding people of the risks. Accidents may cause some workers to resign, and those who stay want to know leaders and management are taking steps to prevent future accidents.

- Reputation: Clients take note of safety records; they understand the consequences of accidents too. If your record is worse than average, you could lose out on future contracts.

- Increased regulatory scrutiny: If the government believes that flaws in your safety program contributed to an accident, it may well try to force you to fix them. Better to get ahead of that headache.

Accidents are called accidents because no one knew they were going to happen. But you can take steps to ensure you have as few as possible.

This article is based on an episode of the No Accident podcast.